Risk Assessment and Other Black Magic: The Pursuit and Defense of the Pernicious

We are living in the middle of a long latency period of chemical, radioactive and genetic experimentation that will eventually provide enough data to demonstrate the dangers of what we are now being exposed to. It is precisely the public's keen awareness of its role as a guinea pig which has eroded confidence in science and in the legitimacy of government regulatory agencies. While scientists in this country decry the infringement on human rights in totalitarian countries, mainly the rights of scientists to freedom of expression, their defense of innocent people in this country who are each day subjected unwittingly to the results of scientific experimentation has been almost inaudible. If science has become discredited, it is not because of so-called "irrational" fear of the unknown but rather because scientists in this country are slow to speak out for the public's right to resist involuntarily imposed harm, and for their failure to spell out the consequences of technological failure.

The fruits of modern science are qualitatively different from those of the past. They have a potential global impact (e.g. weather modification, radioactive and chemical contamination of the food chain, ocean pollution), a genetic impact on future generations (e.g. impoverishment of species, redirection of evolution, and bypassing of natural selection through genetic manipulation), and the trait of irreversibility (e.g. creation of novel organisms, persistent radioactive substances, and toxic synthetic chemicals).

There is no longer any distinction between science and technology or any such thing as "pure" science. Much of modern science, particularly nuclear physics research and molecular biology, involves positive action, not mere thought. For this reason scientists are not absolved from accountability to society or responsibility for their actions.

Because of the potential impact and import of technological consequences–the creation of radioactive wastes, genetic engineering, production and release or carcinogens–those involved in these hazardous enterprises have tried to focus public attention not on the consequences of science applications or their failure but on the probability of accident, error or failure. By so doing, they change the terms of debate, and the dialogue moves away from the question of subjective feelings about risk, ethics, need, or alternative, and into the abstract realm of mathematics, logic, models, and computers, from which realm the ordinary citizen is excluded.

Ingenious exercises are performed by the defenders of the pernicious to minimize, justify, or glorify hazardous technologies and their inevitable by-products; some of these exercises are excruciatingly familiar to us, such as risk analysis and the cost-benefit ratio. In their utilization all of these share in at least one thing: a perversion of the scientific method, where favorable data and studies are selected to support a pet hypothesis ("nuclear power is clean, safe, cheap and necessary"), and contradictory data and studies are ignored or suppressed. An example of the former is the Inhaber study comparing risks of nuclear and solar power; an example of the latter is the long-suppressed WASH-740 update done by Brookhaven National Laboratories.

This massive perversion is not new, for each age and culture has its snake oil salesmen. What is new is the scale of the deception and the encouragement of such trickery through controlled media, government agencies, and corporate subvention by means of grants and contracts.

Risk analysis is no longer the identification of a range of hazards associated with a particular technology, with a view towards minimizing or eliminating the most dangerous or finding alternatives, but rather towards the justification, using numerical mumbo-jumbo and other forms of black magic, of the projects and plans of special interests such as the nuclear power industry, the space colonization freaks, and the pharmaceutical manufacturers.

In this game of power–for it is as much about societal control as profit–risk analysis is an absolute prerequisite since it provides the most secretive and esoteric terminology but disguises the promoters' biases, assumptions and self-interest while evading broader social, political and ethical issues. Thus, risk analysis is less a tool than a complete language that by its nature excludes citizens from social policy making and keeps the ball game in the technical rather than in the political arena.

Control of the game is aided by obscurity of terms, ostensible complexity, and unspoken assumptions which are revealed only to those who know the language and can ask the right questions; those who abide by these rules have already lost the game. Non-quantifiable issues of course cannot be discussed; diversity of subjective opinion on the acceptability of a particular risk is suppressed; goals and values of different sub-groups in society, which often do not coincide with those of others, are not aired. Cooperation in the game of risk analysis requires a priori agreement to discuss only the probability of accident or failure but not the consequences or acceptability of such failure or alternatives. Above all, there is an emphasis on the causes of failure rather than on effects; this is especially true regarding complex systems like nuclear reactors, where the consequences of error or failure, and the difficulty of assessing accident probability, are far greater than in simpler systems.

None of this is very surprising when one looks at who the inventors and users of risk analysis are–not ordinary citizens but precisely those involved in or regulating dangerous technologies. Presumably, if one throws around enough weighty ritualistic jargon, the public can be duped into believing that there actually is such a thing as scientific objectivity. Thus, risk analysis data are highly useful not for being explicit about potential dangers, but just the opposite: for concealing facts, values, opinions, and consequences. A look at the diagram illustrates how the really important information can be hidden and the implicit not made explicit; using such ploys, scientists need not discuss the horrendous consequences of being wrong, such as killing one of the last condor chicks, tainting the human gene pool forever, or irreversibly contaminating the biosphere with radioactive and chemical wastes.

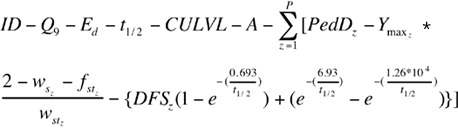

- From the 3-pound report NRC FIN No. A1077 - NUREG/OR-743 - Transportation of Radionuclides in Urban Environments: Draft Environmental Assessment, July 1980. Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, NM, run by Western Electric for the U.S. Department of Energy.

* Groundshine Doses to Pedestrians

Pedestrian groundshine doses are computed using the contamination level on streets and sidewalks (CULVL-DFS, where DFS is the street decontamination factor), with a pedestrian density computed by a time-weighted average of pedestrian densities for each time span in each affected cell (PedD).

where Q9 = units conversion factor -4.39 x -10-5 rem/MeV-uCi-d.

The term ymax in Eq. (37) describes the maximum fraction of the cell covered by the cloud during its passage. The first term in the brackets describes the initial exposure to un-decontaminated ground, and the second term describes the 50-year exposure to decontaminated area.

* (Note: "Groundshine" means radioactivity.)

Another favorite of risk rationalizers is dilution by comparison, using such arguments as: "all activities involve risk"; "there is no such thing as zero risk"; "naturally occurring risks are as bad as man-made ones"; "new risks are acceptable because so many other already exist" (e.g. pre-existing risks justify creation of new ones, ad infinitum), etc. These arguments are too transparent to require response; my only comment here is that the reason the environmental movement arose in the first place was to eliminate or find alternatives to dangerous enterprises. If pre-existing hazards are immutable, then why do so many scientists spend so much time trying to cure naturally occurring diseases?

When confronted with new or controversial technologies, people react in basically one of two ways. One group is skeptical, asks persistent questions of a different kind than those suggested by the technologists, urges restraint regarding undemonstrated projects, looks to evolutionary and cultural experience and tradition, recognizes the omnipresent role of uncertainty and human fallibility (of both human behavior and institutions), is wary of over-enthusiastic claims about "benefits", urges full disclosure of biases and self-interest, respects technical expertise but desires to make the ultimate judgments themselves, resists coercion, involuntary risk and intellectual authoritarianism, balks at taking irreversible steps, and desires to consider the full spectrum of social political consequences of new technology and its impact not only on the individual but on the family, community, human society, the earth, future generations, and non-human species and systems.

The other group unhesitatingly embraces new ideas and projects no matter how untried and speculative, accepts "expert" information from government, media or scientists as "truth", sees science's future as limitless and untrammeled, scoffs at the idea of societal control over science and technology, unquestioningly accepts claims about "benefits", minimizes the imperfections of human beings and human institutions, and in general supports the concept of unrestrained technology in the name of "progress".

For some strange reason the former group is called radical, and the latter conservative. This peculiar switch is hard to explain, except possibly insofar as our society looks at those who challenge existing values and authoritarianism as subversives rather than as valued guides and critics. Our society has a low tolerance for dissent or scrutiny, especially of established religions; perhaps this is because most of its technological enterprises cannot survive close examination, particularly in a broad socio-political context. In another era, the riskers–those who destroy habitat and species by building dams, who produce radioactive waste without knowing what to do about it, who tinker with genes and evolution, who try to hold back the ocean and re-direct the elements–would have been called radical, e.g. disruptive of the established order, subversive of traditional values and adaptive human experience, mockers of useful and necessary emotions like fear and distrust, and promoters of an increasingly lethal society rather than defenders of human health and welfare.

The true conservative–which includes the riskee–demands, at the very least, a demonstration of little or no harm, reversibility, and alternatives. He or she resists coercion, imposition of physical harm and involuntary risk, asking questions about how the proposed action may harm or benefit that person as well as others, and how it will fit in with and sustain societal values and institutions, as well as asking what new kinds of institutions it may require for its acceptance and continuance. The conservative gives more weight to scientific disagreements and the limits of knowledge, rejects the argument that life inevitably involves incremental risks, refuses to justify creation of new risks simply because of pre-existing or unavoidable ones, and seeks, as John Holdren says, to "minimize the social costs of uncertainty", or, as I put it, to minimize the opportunities for mischief.

As for the famed "cost-benefit" ratio, scientists should be very careful when using this, for by implying benefits they imply not the practice of "pure" science but its application. Once these are implied, the benefits, speculative or not, are available for social scrutiny and possibly rejection.

By employing the criterion of usefulness, the scientist becomes personally responsible for the consequences and applications of his work, whether it be atomic bombs or social engineering through genetic manipulation.

Another argument often heard to promote things like nuclear power is that failure to continue it will deprive future generation of this energy source. I need not point out that there is a vast ethical difference between the consequences of not acting and acting. Those who witness a crime without acting to stop it are reprehensible; those who commit the crime are guilty and punishable by law. The future can forgive us for not doing something but never for doing something irreparable and irreversible. In fact, most societies laud those who actively help to prevent violence and physical harm–except ours, which castigates them. For the future, which choice makes sense? To do nothing and deprive it of a (possible) cure for diabetes, or do something and deliver them millions of curies of radioactive substances? Is it better to deprive the future of a cure or deprive them of a catastrophe?

The promotion of lethal technologies by self-interested parties, in the guise of "objective" science, is part of a vaster problem, which I stated previously as the perversion of the scientific method. Konrad Lorenz wrote that it was his habit upon arising each morning to discard a pet hypothesis. Normally most scientists do this when they are faced with non-corroborating data. With nuclear energy, we have the exact opposite: promulgation of an hypothesis (nuclear energy–or nuclear reactor–is clean, safe, necessary), accompanied by a careful selection of those data and studies which support it, and discarding or suppression of those that contradict it. In the former category we have the WASH-1400 Reactor Safety Study, intended by its manufacturers and purveyors to be of "substantial benefit" to the nuclear industry, the infamous, now-retracted Inhaber comparative risk study of nuclear and solar energy, the selective, deliberately incomplete Atomic Industrial Forum study on nuclear and coal plant efficiency, with moral support and propaganda provided by such illustrious bodies as Science, now become house organ for the nuclear industry, and the New York Academy of Sciences' recent Three Mile Island Conference. Simply put, scientists cannot be accepted as both technical experts and proponents, though many of them aggressively seek both these roles. In any case, nuclear power plants are no more or less safe as designed and operated than other machines; but the consequences of failure, human or mechanical, are far greater, and nuclear scientists and engineers cannot be permitted to impose theircriteria of social acceptability of such failure on others.

Some years ago a a group of prominent scientists, including the President of Harvard University, issued a statement in utter seriousness attacking astrology. That they felt compelled to do this at all surprised me, since astrology strikes me as an utterly harmless pastime that imposes no cost or risk on society at large. The thrust of the attack was that the public was being deceived into thinking that astrology was a science, based on scientific "fact" or "truth", whereas it really was based, in their opinion, on irrational faith and superstition. Further comment is really not needed, but it is hard to resist the comment that few things are more irrational than the faith of those in the nuclear establishment regarding the low probability of accidents and the disposal of radioactive waste and its isolation form the biosphere for millennia. And when one sees molecular biologists blithely crossing species barriers and creating new strains of life in test tubes while deprecating a suggestion that such research might create virulent organisms or lead to social misuse of this work, then I wonder which of these schools–the astrologers or the scientists–is based on irrationality and blind faith. Nowadays it is the scientist who mocks what is most natural and useful in man–intuition. Who is deceiving the public more? And which is more dangerous?

Ultimately we must face the real Faustian bargain, which concerns not only knowledge but its control, and must recognize those issues and areas of study where human control may be worse than none at all, especially where it may give the illusion of safety and protection.

In this context some areas of science may have to be placed off bounds, and we may have to recognize that science may have a more limited value to society than scientists would wish, and that people may place other values above those of science. In this respect nuclear energy, recombinant DNA research and its application eminently qualify for exclusion. The by-products of nuclear power affect and control our gene pool by accident, while those of recombinant DNA control it intentionally. And just as humans have always understood the need to protect themselves from natural harm, such as flood, earthquake, hurricane, disease, they must learn, through control and selection of technologies, to defend themselves from man-made harm, which may mean refusing to do certain things at all. Those scientists who do not practice this self-restraint only help to erode scientific legitimacy, and if they persist in calling modern technology too complex for ordinary mortals to understand, then perhaps this automatically may make these technologies unfit for a democratic society.

Questions and Answers

Q: I'd like to compliment you on a very eloquent statement of your views. In fact, I think it's one of the better statements that I've seen along these lines. I'd like to ask, however, whether your opposition to nuclear energy is limited to nuclear reactors or whether you are calling attention to the use of nuclear weapons and our military program as well, which, as I understand it, produces a greater risk than does the civilian program. Which is it?

A: My view are inclusive

Q: You believe the military program should be stopped?

A: Absolutely

Q: How about genetic, say hospital research and things of this nature involving radiation? Do you believe that should be stopped?

A: Medical research, no. I would not terminate it. I think there is a vast difference–technically and ethically, providing that the disposal, the handling of the disposal, of nuclear materials in medicine is done properly, not flushed down the toilet, or out the smoke stack. Actually the disposal of medial waste is far simpler than commercial waste, providing that it is done properly. You are dealing with an individual decision and an individual risk taking rather than one that is generally imposed on society.

Q: I'm not sure I could agree with that, but in reality, how would you obtain the nuclear materials available for medicine?

A: You would have to have a small research reactor to produce those isotopes. It wouldn't have to be on a scale, in terms of size or numbers, of the existing program.

Q: Presuming we eliminate nuclear reactors, should we also eliminate coal-burning power plants?

A: We're getting into a very broad question here which wasn't quite touched on. There again, I follow the concept of soft energy. Given the fact that electricity is not our main problem–liquid fuels is our energy problem–we don't need growth in electricity then we probably don't need much coal either.

Q: You don't feel we need electricity?

A: I think electricity is pretty well saturated. Perhaps not to the utilities' liking in economic terms, but in terms of potential end uses, I think it is at a saturation point, with the exception of possible replacements of older plants. But, even there, I think you will find co-generation and energy efficiency and photovoltaic cutting into that, too. So, if you don't need more electricity, you don't need coal plants either.

Q: Do you feel that there are no growth opportunities?

A: No. I was talking about providing energy services at the point of the end user, that has nothing to do with growth. I can see tremendous growth potential, using the criteria of the previous speaker, for jobs, currency stability and clean environment. I would say that renewable energy, which includes efficiency, cogeneration as well as various forms of solar, fits these goals.

Q: Considering how dilute the solar is on the Earth, I would question that it could serve a very large society.

A: Well, it's dilute but it's quite diverse.

Q: Going back, then, you feel that the existing sources–oil, gas, coal, etc.–are acceptable sources.

A: It depends on the time period you are talking about. I don't think there is any question that we will be in a solar society by the middle of the next century. It is a question of whether we will make decisions between now and then that will enable the peaceful transition with hardship in terms of employment and inflation. I think that is the question. There is no question we will be there. In fact, I've heard many proponents of nuclear technology talk of it as an interim energy source. Although the wastes are not interim, they speak of the technology.

Q: It is my understanding that a coal generating plant will emit more radiation directly into the atmosphere than will a nuclear plant.

A: There are many different kinds of radiation products, some of which are not as intensely radioactive as others. There again, I'm assuming a dirty coal plant and a perfectly operating nuclear plant. If you look at the entire fuel cycle, which on the nuclear side includes the mining of uranium and the creation of mill tailings, which are hazards, then there is no question that there is far more radioactivity of different and more dangerous kinds in the nuclear cycle.

Source: Energy Magazine. Proceedings from 1980 Fourth Annual International Conference on Energy - "The Energy Revolution: Its Impact on Industry and Society".